Equity at the Edges: Who Gets Care and Who Waits

Health access in the Philippines depends heavily on place, income, and identity. Urban residents living near tertiary hospitals encounter long queues yet have multiple options; those in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas (GIDAs) face the opposite problem—few options, sparse transportation, and intermittent services. Indigenous communities and fisherfolk in island barangays often experience delayed diagnosis and treatment, not because of indifference, but because geography and logistics are stubborn adversaries.

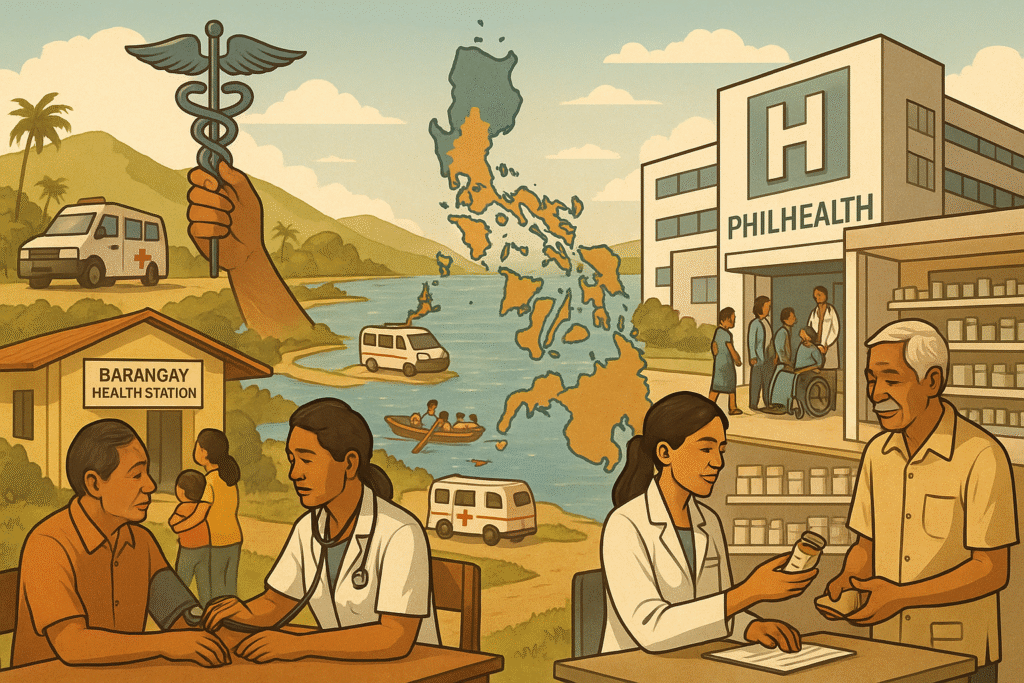

Primary care is the entry gate, but capacity differs dramatically. Barangay Health Stations and Rural Health Units provide immunizations, prenatal services, and basic consultations, yet many lack consistent diagnostics, maintenance medicines, and cold-chain reliability. In some municipalities, outreach teams and mobile clinics bridge the gap; in others, staffing shortages and budget constraints limit frequency, leaving chronic conditions unmanaged for months.

Financial barriers persist despite insurance. PhilHealth boosts protection through case-based payments and primary care benefits, but households still shoulder out-of-pocket spending for medicines, laboratory tests, and transport. Informal workers and the near-poor are particularly vulnerable to spending shocks: a single hospitalization can wipe out savings, while repeated travel for specialist referrals strains income.

Cultural and language considerations shape utilization. Indigenous peoples may distrust facilities if staff do not respect traditions or communicate clearly. Health education delivered through local leaders, in familiar languages, increases early care-seeking. Community health workers—when equipped and supervised—act as trusted bridges, tracking pregnancies, following up on tuberculosis contacts, and demystifying hypertension management.

Diagnostics and specialist access create chokepoints. Ultrasound, X-ray, and advanced labs cluster in cities. Telemedicine can partially offset this by connecting rural clinicians to specialists, but bandwidth, device availability, and referral feedback loops must be dependable. Without reliable follow-through, advice stays theoretical, and complications accumulate.

Medicines are a constant stressor. Even where the Essential Drug List guides procurement, stockouts force patients to buy from private pharmacies at higher prices. Promoting quality-assured generics, pooling procurement across localities, and publishing price and stock dashboards can lower costs and restore confidence. For chronic diseases, synchronized refills and community pick-up points reduce missed doses.

Equity also hinges on disaster readiness. Typhoons, floods, and earthquakes can sever communities from care overnight. Facilities built or retrofitted to withstand hazards, pre-positioned supplies, and pre-arranged transport agreements help maintain continuity. Post-disaster surge teams and mental health first aid address both physical and psychosocial impacts.

The path forward is targeted: deploy multidisciplinary primary care teams in GIDAs with incentives for rural service; expand transport vouchers for referrals; integrate telehealth with clear escalation protocols; and give communities a seat at the table through local health boards. When the most remote and marginalized are served well, everyone else benefits from the same systems that make care reliable.