Spice Routes to Supper: How History Built Malaysia’s Table

Malaysia’s cuisine did not emerge overnight. It is the edible record of trade winds, pilgrim routes, and port cities, shaped by the Malacca Sultanate’s heyday, British colonial corridors, and continuous migration from China, India, and the Indonesian archipelago. Each wave brought new techniques and ingredients, then blended with local produce—coconut, rice, herbs, and seafood—to form a living culinary language.

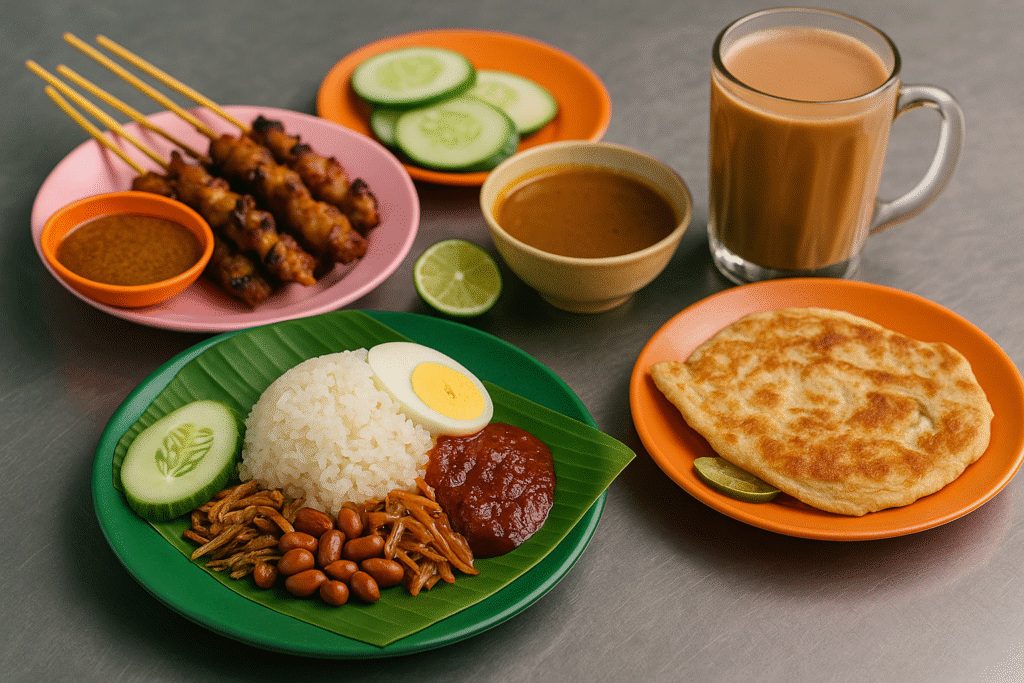

At the heart of the Malay repertoire sits the rempah: spice pastes pounded from shallot, garlic, ginger, chilies, lemongrass, galangal, and turmeric. Fry those pastes until aromatic, and you have the base for countless classics. Consider rendang—beef or chicken slowly reduced in coconut milk with kerisik (toasted coconut), aromatics, and spices until the sauce caramelizes and clings. Or nasi lemak, whose pandan-scented rice, sambal, anchovies, peanuts, and cucumber compose a complete lesson in contrast: creamy versus hot, crunchy versus soft.

Chinese arrivals—Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese—brought the wok, noodle craft, and an instinct for searing heat. Char kway teow relies on “wok hei,” that smoky kiss from a blazing pan, as flat rice noodles tangle with prawns, cockles, chives, and soy. Hokkien mee in Kuala Lumpur folds thick noodles into a glossy, dark soy glaze with cabbage and pork or halal alternatives. Hainanese cooks helped seed kopitiam culture (coffee shops) and perfected silky poached chicken with fragrant rice—chicken rice that is now a national comfort dish.

Indian influences arrived in many streams: South Indian vegetarians; Tamil Muslim traders who evolved into the beloved mamak culture; North Indian spice sensibilities. Roti canai is a masterclass in lamination—ghee-brushed dough slapped and griddled, ready to tear into dhal or curry. Nasi kandar, born from Penang’s Tamil Muslim vendors, lets you “banjir” (flood) your rice with multiple gravies—fish head curry, ayam ros, squid sambal—each with a distinct spice profile. Teh tarik, the showy “pulled” tea, speaks to the mamak stall’s sociability as much as its taste.

Peranakan (Nyonya) cooking exemplifies fusion before fusion was a buzzword: Chinese techniques meet Malay spice cupboards. Dishes like ayam pongteh (soy-braised chicken with fermented bean paste), laksa Nyonya, and jewel-toned kuih (pandan, coconut, gula Melaka) highlight balance and craft. In Melaka, Portuguese Eurasian families contributed devil curry (kari debal) and baked sweets, while Javanese and Bugis lines introduced satay, soto, and lontong to Malay tables.

Across the South China Sea, Indigenous communities of Sabah and Sarawak deepen the story. Manok pansoh (chicken cooked in bamboo), kolok mee (springy noodles with light sauce), umai or hinava (citrus-cured fish), and ingredients like tuhau (ginger-lily stems), bambangan (wild mango), and Bario highland rice create a distinctive Bornean cadence. Thread it all together and the picture is clear: Malaysia’s table is a map. To eat here is to tour centuries of exchange, anchored by local terroir and an unshakable love of balance—sweet, sour, salty, spicy—held in harmony by coconut, tamarind, and time.